Persistent Anovulatory Follicles

By Jos Mottershead

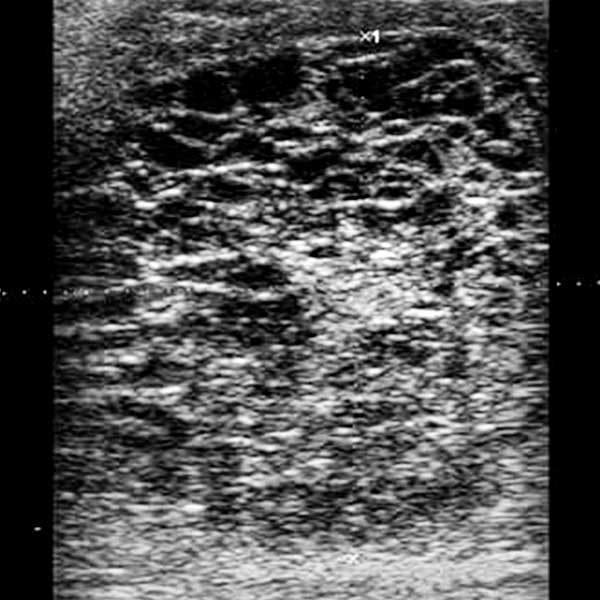

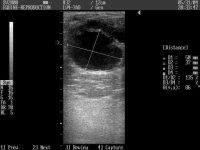

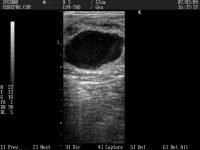

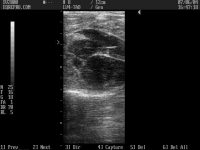

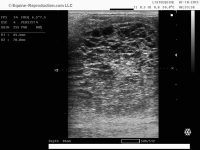

You’re following a mare’s follicular development using ultrasound prior to breeding and are relieved to see a good sized follicle developing. Unusually, the follicle continues to develop beyond the size at which you normally see ovulation occurring in this mare, and the development seems to continue for an inordinate amount of time. If using transported cooled semen, you may call for a shipment and inseminate at least once possibly twice, anticipating an ovulation which doesn’t occur. Then something strange seems to happen to the follicle when being viewed using ultrasound. Not only has it not ovulated and grown to be abnormally large for the mare, but it is starting to develop white specks within the dark follicular fluid. What is going on?

Anovulatory Hemorrhagic Follicles (AHF), “PAF” or “LUF” – The Difference

In all likelihood, you are seeing a condition known as a “persistent anovulatory follicle” (PAF). Also termed an “Anovulatory Hemorrhagic Follicles (AHF)” – or the variant “HAF”. Colloquially, it may be referenced as an “autumn follicle”. It has been suggested that a further subdivision may be made clarifying a division between those which develop luteal tissue and those which do not. If this descriptive division (which we support) is to be used, the former should be referenced as a “LUF” – luteinized unruptured follicle – and the latter by the AHF term, while collectively they can be known as “PAFs”. Luteinized Unruptured Follicles are a condition found in the human female, and the corresponding state in the equine has been suggested as a possible model for research in the human1. This terminology clarification has importance when it comes to possible resolution of the structures, as described below.

Persistent Anovulatory Follicles – Cause

It is unclear exactly what causes a persistent anovulatory follicle, but suggested possibilities include low follicular estrogen levels 2; insufficient gonadotropin stimulation (which can result in low follicle stimulating hormone – FSH – and/or luteinizing hormone – LH – levels) 3; low prolactin levels4; or hemorrhage into the interior (lumen) of the follicle 5 – the initial specks that appear on ultrasound in an AHF are considered to be blood, and the subsequent strands which appear, fibrinous. There has been a degree of correlation between those animals that have received hCG or GnRH in an attempt to stimulate ovulation or those which received a luteinizing hormone to promote onset of estrus6. It should be noted however that the condition will also develop in mares that have not received any promotional drug, nor is the incidence significant enough to consider not giving such drugs at all unless significant repetition occurs withint he individual mare. PAFs have also been experimentally induced in mares by giving high doses of Flunixin meglumine (“Banamine”, “Finadyne” etc.) during the immediate pre-ovulatory period7. The incidence of naturally occurring PAFs is more common in the transitional phases of the year – both spring and fall, hence the name “autumn follicles” – as well as in older mares.

PAFs have been shown as occurring in over 8% of estrous cycles with age differentials recorded as below. An overall recurrence of 43.5% in the same breeding season has been found8.

| 6-10 years old | 16-20 years old | mean age of PAF mares |

| 4.4% | 13.1% | 15.4 +/- 5.5 years |

Anovulatory Hemorrhagic Follicles (AHF) or LUF – Effect and Resolution

One frustrating aspect of these PAFs is that they are not fertile (as there is no ovulation), so the cycle on which they occur is lost. Many also result in a delay in return to subsequent estrus, so future breeding may also be delayed. About 85% of PAFs do develop luteal tissue (the tissue that becomes present when a mare normally ovulates – that luteal tissue being contained within the corpus luteum or “CL”) which is evidenced by the follicle showing a fully anechoic appearance on ultrasound and elevated levels of P4 (>1 ng/ml) in a blood-progesterone assay. These luteal structures – “LUFs” (“luteinized unruptured follicles”) – may respond to treatment and resolve if a luteolytic dose of prostaglandin F2α is given. The remaining 15% however, which retain an anechoic appearance on ultrasound, will remain in situ despite all attempts to dislodge them – in some instances for as long as 100 days. Strictly speaking, this is the differential between the correct usage of “AHF” or “LUF”. The AHF is the structure which fails to ovulate and develops blood specks and fibrin strands, and does not develop luteal tissue (so will not respond to PGF2α); whereas the “LUF” while it also does not ovulate, does develop luteal tissue and will therefore be likely to respond to PGF2α.

Our standard protocol when seeing one of these structures is to check again in a couple of days to determine that it is indeed a PAF, and if this is confirmed we commence micro-dosing the mare with a 1/10th of the normal dose of prostaglandin F2α on a daily basis until resolution starts to appear or 14 days is reached – whichever happens first. By using micro-doses, we are avoiding the unpleasant side-effects often seen with the full dose of prostaglandin F2α in the mare (sweating, cramping etc.), while still providing a luteolytic dose which will have an effect on luteal tissue if present. If the structure has not resolved after 14 days of treatment, we presume it to be non-luteal.

It should be noted that if the structure is non-luteal (i.e. not a “LUF”), then it is possible that a second follicle will form and the mare enter (or remain in) a true estrus – endometrial edema visible per ultrasound and cervical relaxation with positive response to the stallion. If this happens, in many cases, the subsequent follicle may mature and ovulate normally, and a pregnancy be established if suitable breeding takes place. This is one reason why continued monitoring of these structures using ultrasound may be of value.

For years, the presence of a condition known as “cystic follicles” in the cow has been considered to be absent in horses, although there have been occasional incidences of such a diagnosis being made. The research performed at Colorado State University suggests that while strictly speaking, a “cystic follicle” is still almost unknown in the equine, there may be a correlation between these anechoic equine PAFs or Anovulatory Hemorrhagic Follicles (AHF) and follicular cysts in cattle, and the echoic equine LUF and bovine luteal cysts8.

Note: It is important not to erroneously identify a PAF as a granulosa cell tumour based upon ultrasound images. It is not uncommon for the two to have a similar ultrasonic “honeycomb” like appearance, but clearly the treatment and outcome are going to be very different! Of note too is that pregnant mares will often exhibit what appears to be a LUF in the period after the formation of the endometrial cups when secondary CL activity is important for pregnancy maintenance. This is completely normal, and again must not be mistaken for either a problem or a GCT!

References:

1: Bashir ST, Gastal MO, Tazawa SP, Tarso SGS, Hales DB, Cuervo-Arango J, Baerwald AR, Gastal EL. 2016. The mare as a model for luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome: intrafollicular endocrine milieu. Reproduction 151(3):271-83

2: Pierson RA. Folliculogenesis and ovulation. In: McKinnon AO, Voss JL editors. Equine Reproduction. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 1993. p 161-71.

3: McKinnon AO. Ovarian abnormalities. In: Ranaten NW, McKinnon AO, editors. Equine diagnostic ultrasonography. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1997. p 233-51.

4: Zagrajczuk A. Personal Communication.

5: Ginther OJ. Reproductive biology of the mare. Basic and applied aspects. Cross Plains, WI: Equiservices, 1992.

6: Cuervo-Arango J, Newcombe JR. 2009. The effect of hormone treatments (hCG and cloprostenol) and season on the incidence of hemorrhagic anovulatory follicles in the mare: a field study. Theriogenology 72(9):1262-7

7: Cuervo-Arango J, Newcombe JR. 2012. Ultrasound characteristics of experimentally induced luteinized unruptured follicles (LUF) and naturally occurring hemorrhagic anovulatory follicles (HAF) in the mare. Theriogenology 77(3):514-24.

8: McCue PM, Squires EL. 2002. Persistent anovulatory follicles in the mare. Theriogenology 58;541-543.

© 2002, 2007, 2021 Equine-Reproduction.com, LLC

Use of article permitted only upon receipt of required permission and with necessary accreditation.

Please contact us for further details of article use requirements.

Other conditions may apply.