The Effect of Uterine Interference on Reproductive Function in the Mare

An unpublished manuscript written in 1976

by

John R Newcombe and W E Allen, Royal Veterinary College University of London

Introduction

It has been shown in several recent reports that irrigation or infusion of the uterine lumen of the mare during the luteal phase of the oestrous cycle causes an earlier return to oestrus and ovulation than would be normally expected1,2. Indeed, for many years, sterile saline irrigation has been used as a method of induction of oestrus in anoestrus mares during the breeding season. It has also been shown that this is the result of regression of the corpus luteum and fall in blood progesterone levels. To be effective irrigation must be performed during the period of luteal dominance.

Reason for Study

This laboratory has made three significant observations:

- Irrigation or any other uterine interference made during the luteal phase was inevitably followed by a bacterial endometritis

- The oestrous cycles of infected mare were shorter than that of normal non-infected mares, Slide 1 (lost) shows the lengths of oestrous cycles in normal mares observed closely over a three year period at this Institution

- Subsequent blood progesterone values showed a premature decline following interference.

M&M

A herd of Welsh Section A and B type pony mares was maintained outdoors under ambient conditions for teaching and research purposes at the Veterinary School

Mares were examined per rectum daily follicle growth and ovulation were detected. The position of the developing corpus luteum was noted also its size and consistency was found that the CL was then palpable for a period of days initially as a distinct rubbery body but regressing to a definite soft area in an otherwise hard ovary. In all cases the CL was still detected up to Day 10 and later in some.

Blood samples were assayed for progesterone levels by a competitive protein binding assay and expressed in ng/ml. The end of the luteal phase was defined as the first time that levels fell to or below 1 ng/ml.

Mares were followed to detail normal reproductive parameters or subjected to various investigations which included cervical and endometrial swabbing, uterine saline infusion and uterine biopsy. Prior to these investigations, the vulval surface was cleansed thoroughly with soft soap. The cervix was illuminated through a narrow plastic speculum, and bacterial swabs taken on the end of a 50 cm wire, either from the external cervical canal or if possible, from the uterine lumen

Mares were diagnosed as infected by the culture of swabs from the external cervical canal in dioestrus or the uterine lumen during oestrus taken 24 or 48 hours later. Swabs were routinely cultured aerobically directly onto Sheep Blood Agar and McConkey Agar. Further identification was made using Deoxycholate citrate agar, Mannitol Salt Agar, etc. A positive identification of bacterial infection was the culture of multiple colonies of either or both Streptococcus zooepidemicus or Escherichia coli. Other species were often concurrently cultured including Strep. equisimilis, Staph. alba and various alpha and non-haemolytic Streptococci. Indefinite cultures were investigated by identification of neutrophils on a smear.

Results

Mares became infected spontaneously and experienced clinical symptoms of endometritis during the luteal phase subsequent to either natural service or post-partum complications. Infection also followed any form of intra-luminal uterine interference, such endometrial swabbing, biopsy or uterine irrigation.

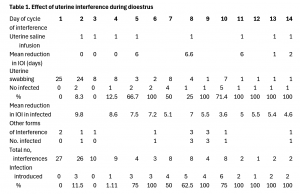

In mares that were infected from oestrus or by uterine interference during dioestrus, the CL was detected up to Day 8 but never detected after Day 10. Table 1 details the effects of uterine interference during dioestrus. The maximum number of days remaining palpable was 10 to 11 for normal cycles but only 7 to 8 for infected cycles. However, when infection was not induced until Day 9, the CL remained palpable for up to 3 days in one mare. The mean length the CL the remained palpable was 8 days for infected mares, 12 days for normal mares, 13.4 days for pregnant mares and 13.5 days for mares in prolonged dioestrus. Prolonged dioestrus was defined by continued peripheral P4 values above 1 ng/ml and maintenance of a clinically dioestrus state.

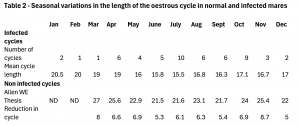

The length of the luteal phase from ovulation to P4 > 1 ng/ml was 16+/- 1 day in normal mares and 8.5 days in infected mares. Oestrous cycle lengths (IOI) were shorter by a mean 6.4 days (Table 2)

Graph (not available) shows that P4 values were the similar up to Day 6 after which they fell in the infected mares, whereas in normal mares P4 values remained elevated until after Day 14. The abrupt fall seen in individual mares was exemplified when values were synchronised to the Day of luteolysis. The same abrupt fall to 1 ng/ml within 48 hours was seen in mares subjected to any transcervical uterine interference.

Conception rates of 61% in mares subjected to interferences up to and including Day 4 compared favourably with those in normal mares not subjected to interference (Table 3). However, following interference from Day 5, only 1 of 13 mares conceived (7.7%). Only one of the 36 mares ‘ interfered’ on Day 1-4 became infected while only 2 of the 13 ‘interfered’ on Days 6 to 28 were not infected (Day 8 pregnant and Day 20)

Discussion (in the light of modern science!)

Uterine irrigation for return to cyclicity of anoestrus mares during the breeding season has been practised for many years3,4. The procedure was highly effective although F.T. Day also commented that a vulval discharge was noted in a few!5

It had been proposed and presumed that saline irrigation exerted an inflammatory effect upon the endometrium with consequence release of prostaglandin. This theory was justified by the fact that non-buffered saline is fractionally acidic! We now know that under strict hygienic precautions, bacterial contamination of the uterus during embryo flushing and transfer can be avoided. However, during these studies, it was initially assumed that the hygienic procedures adopted were sufficient. It was subsequently discovered that the method of cervical swabbing although apparently hygienic, often included pre-swab contamination of the external cervix by bacteria transferred from the vulva/vestibule during introduction of the speculum. The swab could then transfer bacteria from the cervix to the endometrium.

Recent addition to the script

Ball et al. in 1987 found 4 of 12 control mares became infected following inoculation if 1 ml PBS6. The accidental contamination of the lumen is always possible despite the most hygienic precautions hence its is usually accepted practise to induce luteolysis with PFG after an embryo flush.

The study showed that uterine interference in the first 4 days of dioestrus (despite inadequate hygiene) did not cause infection and did not affect the chance of conception. From Day 5 onwards with significantly elevated P4 levels, any form or uterine interference whether it be by catheter, swab or even a contaminated finger during cervical exploration, was highly likely to induce a bacterial endometritis.

Cultures in this study revealed that only two organisms seemed to be the primary factors in endometritis and although other species may be co-cultured, no other species appeared to be a primary pathogen. Experiments inoculating a broth of Streptococcus zooepidemicus during dioestrus (> Day 4) caused a rapid acute inflammation as evidenced by a purulent discharge, a palpable increase in uterine tone and diameter, loss of a palpable CL and an early return to oestrus. Similar clinically to uterine interference but more rapid in onset

Conclusions

The effect of saline infusion to cause premature return to oestrus in dioestrous mares or the termination of prolonged dioestrus and ‘lactational anoestrus’ is the result of unintentional introduction of part of the vulval flora of which two organisms proliferate causing acute inflammation. The procedure is only effective when a bacterial inflammation results. The resulting inflammation causes a premature release of a luteolysin which is presumed but at present has yet to be proven, to be a prostaglandin.

References:

1: Arthur GH Induction of oestrus in mares by saline infusion Vet Rec 86: 584 1970

2: Arthur GH Influence of intrauterine saline infusion upon the oestrous cycle of the mare, J Reprod Fert Suppl 23 (1975) 231-234

3: Proctor DL (1953) Sterility in mares. Proc 90th Ann Meet Am vet med Ass p 40

4: Day FT (1957) The veterinary clinician’s approach to breeding problem mares, Vet Rec 69:1258=1267

5: Day F. T. Practitioner at Day and Crowhurst Newmarket England

6: Ball BA, Shin SJ, Patten VH, Garcia MC and Weeds GL (1987) Intrauterine inoculation of Candid parapsilosis to induce pregnancy loss in pony mares, J Reprod Fert Suppl 505-506

© 1976 Professor John Newcombe & Dr. W.E. Allen, BVetMed, MRCVS

Edited, 2025 by Professor John Newcombe