Bacterial Infection of a Stallion’s Reproductive Tract

A bacterial infection of a stallion’s reproductive tract is comparatively rare. When present, one of the first indicators is often the condition of the semen, or in the case of live cover where semen is not being evaluated, reduced or negated pregnancy rates. Tract infections may produce no obvious external signs, or may present with inappropriate swelling of the testicles and sheath. Infections can be difficult to resolve owing to an inability to easily produce adequate minimum inhibitory concentrations of antibiotic in the tissues involved.

Case Report

Affected Animal:

An actively breeding seven year-old AQHA stallion

History:

The stallion was presented to the clinic with a request to collect semen for artificial insemination. The stallion had been collected two seasons earlier by the facility, demonstrating low-normal volume (gel-free 20 ml; 30 ml gel) with good total sperm numbers (12.6 billion) in the ejaculate, good total motility and low average progressive motility (88/34) established by Hamilton Thorn CEROS CASA. The following season he was collected twice for insemination, with notably lower quality ejaculates (1: 72 ml, 4.97 billion, 31/10 and 2: 30 ml, 2.7 billion, 74/36 – neither ejaculate containing gel fraction). Pregnancies were established. The reduced quality of the ejaculates was put down to the stallion having been actively pasture breeding immediately prior to being presented for semen collection. A more detailed semen evaluation was not performed.

Case Presentation:

The stallion was presented for semen collection for the third consecutive season. Sexual behavior, response time and external genitalia appearance were all normal. The volume of the ejaculate was low (5 ml gel-free, 20 ml gel) with poor concentration (<20 million/ml). It was determined that the stallion had been pasture breeding up until the morning of being brought to the clinic for collection, and while not observed breeding that morning, had been turned out with mares in estrus until removal for transport. The recommendation was made to the client to return for another collection after several days sexual rest (i.e. not being turned out with a mare or hand-bred). Further evaluation was not performed.

Culture Plate Showing Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth (Sun14916 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0)

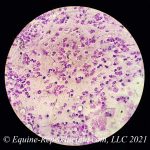

The stallion returned 6 days later with assurances that he had not been bred. Again, sexual behavior and collection time was normal. The ejaculate volume was high – 120 ml – although the stallion had not been excessively teased. The color of the ejaculate was cream, with a thick consistency. An immediate visual impression was that this ejaculate consisted of a significant portion of inflammatory cells, if not in entirety. A sample was stained with a Romanowsky-type differential stain (generic “Diff-quick”) which confirmed a high number of inflammatory cells with only a few sparse sperm cells visible. Immediate cessation of pasture breeding or any form of breeding was recommended, with a referral being made to the local University Veterinary Teaching Hospital.

Diagnosis:

The University Veterinary Teaching Hospital isolated a heavy Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth from the semen and urethra. Further diagnostics were not requested by the stallion owner. After discussion with the client, a recommendation of systemic antibiotics with re-evaluation was given. A presumptive diagnosis of Seminal Vesiculitis and/or Ampullitis as described by Blanchard et al[1] and others would not be unreasonable.

Prognosis:

Potential for future fertility was considered dubious and dependent upon response to the antibiotics. If breeding was to be attempted, it was recommended that the stallion be used only for AI and that his semen be fractionated during collection (to capture only the sperm-rich fraction)[2] and stored for up to 4 hours (recommended minimum being 20 minutes[3]) in semen extender containing antibiotics to which the Pseudomonas aeruginosa had shown sensitivity prior to insemination.

Treatment:

Systemic antibiotic treatment with an antibiotic to which the pathogen showed sensitivity was initiated.

Result:

Resolution was not apparent, and the owners elected to castrate the stallion.

Discussion:

While the origin of the pathogen could not be definitively identified, suspicion has to be placed on one or more of the mares which were being pasture bred, as none had clitoral or uterine swab cultures performed prior to being exposed to the stallion. Alternatively, the pathogen could have been encountered environmentally, and subsequently transferred to the mares by the stallion or vice versa. Pregnancy rates for the season were markedly low, and at least one mare was subsequently known to have aborted. The situation with this stallion, while comparatively rare, underlines the importance of pre-breeding evaluations of both mares and stallions and highlights the risks associated with indiscriminate and repetitive pasture breeding practices.

Other Comments:

As noted, bacterial infections of a stallion’s reproductive tract may not be easily resolved, as establishing minimum inhibitory concentrations of antibiotic in the affected tissues can be difficult. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative and ubiquitous environmental bacterium often found in soil and water. It is considered to be an “opportunistic” pathogen and to compound the limitations related to adequate tissue antibiotic levels being reached, it is a potent biofilm producer. This may further limit antibiotic efficacy. The species name aeruginosa is a Latin word meaning verdigris (“copper rust”), referring to the blue-green color of laboratory cultures of the species. This blue-green pigment is a combination of two metabolites of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, pyocyanin (blue) and pyoverdine (green), which impart the blue-green characteristic color of cultures.[4]

Additional diagnostic work could have included ultrasound and endoscopy of the reproductive tract to isolate the precise location of the infection. Dependent upon those findings, additional treatment options might have included endoscopic flushing with LRS followed by antibiotic infusion. While this treatment is possibly beneficial, it has also been shown to be potentially ineffective over a period of time, and that semen quality may again decline with recurrence of the condition.[5]

If a short-term resolution of the bacterial presence could have been achieved following antibiotic treatment, cryopreservation of semen may also have presented an option for future use of the stallion’s genetics.[6]

References:

1: Blanchard TL, Varner DD, Hurtgen JP, Love CC, Cummings MR, Strezmienski PJ, Benson C, Kenney RM. 1988. Bilateral seminal vesiculitis and ampullitis in a stallion. J Am Vet Med Assoc 15;192:525-6.

2: Oliveira SN, Andrade Jr LRP, Araujo EAB, Silva LFM, Rayashi RM, Alvarenga MA, Dell’Aqua CPF, Dell’Aqua Jr JA, Canisso IF, Papa PM, Papa FO. 2018. Fractionated Semen Collection Improved Fertility of Stallions With Seminal Vesiculitis. JEVS 66:78 (Proc. XIIth ISER).

3: Blanchard TL, Varner DD, Love CC, Hurtgen JP, Cummings MR, Kenney RM. 1987. Use of a semen extender containing antibiotic to improve the fertility of a stallion with seminal vesiculitis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Theriogenol. 28, 541-546.

4: Henry R. 2012. Etymologia: Pseudomonas. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18 (8): 1241

5: Sancler-Silva YFR, Monteiro GA, Ramires-Neto C, Freitas-Dell’aqua CP, Crespilho AM, Franco MMJ, E R Silva-Junior ER, Cavalero TMS, Scheeren VFC, Papa FO. 2020. Does semen quality change after local treatment of seminal vesiculitis in stallions? Theriogenology 144:139-145

6: Sancler-Silva YFR, Monteiro GA, Ramires-Neto C, Freitas-Dell’aqua CP, Crespilho AM, Franco MMJ, E R Silva-Junior ER, Cavalero TMS, Scheeren VFC, Papa FO. 2020. Does semen quality change after local treatment of seminal vesiculitis in stallions? Theriogenology 144:139-145

© 2022 Equine-Reproduction.com, LLC

Use of article permitted only upon receipt of required permission and with necessary accreditation.

Please contact us for further details of article use requirements.

Other conditions may apply.