Late Term Pregnancy Problems in the Mare – Ventral Rupture in the Mare

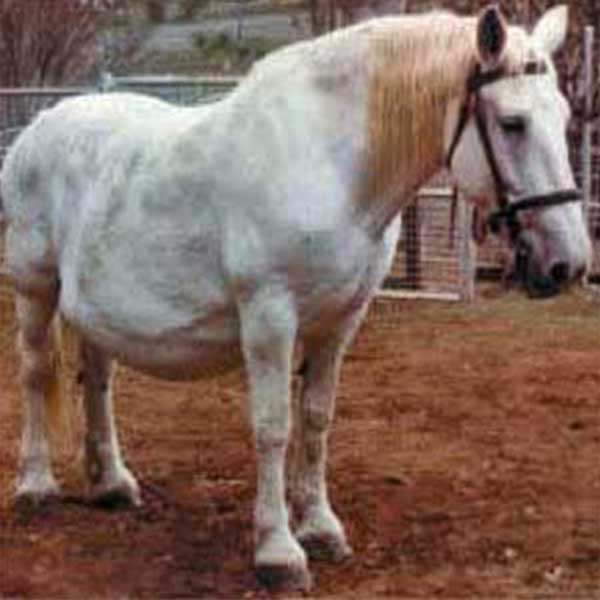

The 19-year-old multiparous pregnant Percheron mare illustrated here is presented to you with a rapidly enlarging abdomen. The owner is concerned about the abrupt development of an extensive area of painful oedema on the ventral abdominal wall. She is 325 days from the last covering date and has exhibited increasing depression and discomfort during the previous 24 hours. Rectal examination found a presenting foal with head and legs inside the pelvis, the foal moved vigorously when touched, the cervix was slightly dilated. Ultrasound examination of the enlarging abdomen showed the possibility of fluid, most likely blood, extravasated into the abdominal tissues. Over the next half hour, the mare’s heart rate increased to 70/minute and respiratory efforts became more laboured with further signs of developing depression.

The 19-year-old multiparous pregnant Percheron mare illustrated here is presented to you with a rapidly enlarging abdomen. The owner is concerned about the abrupt development of an extensive area of painful oedema on the ventral abdominal wall. She is 325 days from the last covering date and has exhibited increasing depression and discomfort during the previous 24 hours. Rectal examination found a presenting foal with head and legs inside the pelvis, the foal moved vigorously when touched, the cervix was slightly dilated. Ultrasound examination of the enlarging abdomen showed the possibility of fluid, most likely blood, extravasated into the abdominal tissues. Over the next half hour, the mare’s heart rate increased to 70/minute and respiratory efforts became more laboured with further signs of developing depression.

QUESTIONS

- What could be the likely clinical conditions present?

- How would you differentiate these conditions?

- What are some of the predisposing factors?

- What supportive measures would you undertake in the early stages?

- What factors must be considered prior to the induction of parturition in the mare?

ANSWERS

1. Any late-pregnant mare presenting with a rapidly enlarging abdomen and often an area of painful oedema along the ventral abdominal wall could be suffering from rupture of the abdominal musculature (oblique and transverse abdominal muscles: a ventral hernia) or rupture of the rectus abdominis muscle or rupture of the prepubic tendon. These can occur together or separately in pregnant mares. In practice, ventral herniation, rupture of the rectus abdominus muscle and rupture of the prepubic tendon can be considered as one condition under the collective heading of ventral ruptures. This would seem a reasonable approach, as the conditions are all defects of the abdominal wall. There may be some obvious clinical differences in presenting signs as discussed below. Other clinical conditions would include haematoma – subcutaneous or intramuscular and placental hydrops as a primary cause leading to the above.

2. This is a difficult diagnostic dilema and rectal palpation is usually unrewarding due to the advanced state of the pregnancy although the fetus can usually be palpated. Ventral rupture in the mare presents as ventral oedema from the udder to the xiphoid cartilage of the sternum. The typical presenting sign noticed by the owner is a sudden alteration in the contour of the ventral abdomen. There will be signs of distress and intermittent colic. If the pain is severe, there will be an increase in heart rate and respiratory rate. These mares are generally reluctant to move, walking slowly and lying down for long periods of time. Body temperature is usually normal. The presence of a severe plaque of ventral oedema (see illustration) and progressive distortion of the mare’s abdominal shape often makes manual palpation of the area unrewarding. Deep palpation may be resisted as it is painful. Ultrasonographic examination of the posterior aspect of the ventral abdomen may be useful to detect the presence of a hernia. Ultrasonography may also reveal the size of the defect and the structures involved. Any defect in the abdominal musculature may be complicated by bowel incarceration. All examinations are less than satisfactory due to the foal’s presence and oedema of the body wall. Rupture of the prepubic tendon causes development of signs similar to those associated with ventral hernias. Some differences may be present, but these may not be readily noticeable. Due to loss of tension from the cranial aspect of the pelvis, the pelvis will appear tilted in cases of prepubic tendon rupture. The tail head and ischial tuberosities may be elevated. Some mares develop very obvious lordosis and adopt a “rocking horse” position (see illustration) because the pelvis and vertebral column cannot maintain normal alignment. The udder may be displaced cranially and ventrally because of loss of its caudal attachment to the pelvis. The plaque of oedema can almost obliterate the outline of the mammary gland (see illustration). Rupture of the prepubic tendon may easily lead to rupture of the blood supply to the mammary gland and haemorrhage of the adjacent musculature. Blood may be detectable in the milk. Together with the reluctance to walk and lie down, these signs are strongly indicative for rupture of the prepubic tendon.

3. In most cases, there is no apparent predisposing cause for ventral rupture in the mare. Predisposing factors include pathological pregnancies with increased uterine weight such as hydrops of the fetal membranes. Twin pregnancy and trauma in late pregnancy also increase the incidence. The condition seems to be more common in older, unfit mares and, probably because of their size, draught horses. Affected mares are generally close to term.

4. Initial treatment for ventral rupture in the mare is aimed at stabilising the horse by restricting activity to a small yard or large stable. It is important to closely monitor for signs of blood loss, constipation, loss of protein and any development of further discomfort. Anti-inflammatory drugs may help relieve the discomfort. Use of a strong bandage around the abdominal wall acting as an abdominal sling may provide support for the ventral abdominal wall. However, such bandages are rarely successful except in mild cases where the mare is in good health and in many cases these mares usually manage without support. Any abdominal bandage must be well padded to avoid pressure necrosis along the backline. A laxative, high concentrate diet may assist in decreasing the bowel contents and reducing the degree of abdominal exertion associated with defecation. The possibility of bowel entrapment and strangulation should be investigated and surgical correction performed where appropriate. In many cases, due to rapidly changing clinical parameters, the mare gains little from supportive treatment and induction of parturition (or termination of the pregnancy in mares earlier in gestation) must be performed. Assistance with parturition is always necessary as the mare is likely to experience difficulty in inducing sufficient abdominal pressure to deliver the fetus. If the fetus is sufficiently mature, the foal will generally progress well after induction of parturition. The oedema usually resolves quickly after foaling and the mare can suckle the foal normally. It is advisable to check the foal’s antibody levels at 36 hours of age because the oedema present immediately after parturition may interfere with colostrum intake. Supplementation with colostrum or plasma may be indicated. In situations where the mare and foal progress well, the owner may be tempted to re-breed the mare. This must be strongly discouraged due to the likely re-occurrence of the condition. If breed society regulations permit it, embryo transfer offers a very useful option in these mares. Surgical repair of small ventral hernias may be possible using primary closure or mesh herniorraphy has been reported. Except where the defect is particularly small, rebreeding the mare is not to be recommended due to the possible exacerbation of the condition by further pregnancies. In any case, the pregnancy would need constant monitoring. Surgical repair of small defects should not be attempted until several weeks after parturition to allow oedema to subside and fibrosis of the hernial ring to occur. Spontaneous healing of partial ventral hernias can occur. In almost all cases surgical repair of prepubic tendon rupture is not possible and euthanasia may be necessary.

5. It is important to note that there is an increased risk of delivery problems (dystocia and retained fetal membranes) and the presentation of a premature foal when parturition is induced. Parturition induction is therefore rarely indicated in the mare and it is recommended that it be performed only under closely controlled conditions and in exceptional circumstances. To indicate fetal maturity there should be:

- Adequate mammary development with good quality colostrum with Calcium concentration > 40 mg/dl;

- A gestation length in excess of 330 days

- Relaxed cervix

Once induction has begun, the foaling is the responsibility of the veterinarian and they must remain close at hand until the process is complete. Progress should be regularly monitored by vaginal palpation and it is important to remember that expulsion of the foal may require some assistance. Synthetic prostaglandins have been used in the past, but have been associated with serious complications such as poor fetal viability. Similarly corticosteroids are not recommended for induction of parturition.

© 2003 Dr. Jonathan F Pycock, B.Vet.Med., Ph.D., D.E.S.M., M.R.C.V.S.

Presented here with the author’s permission.