Retained Fetal Membranes in the Mare

By Dr. Jonathan F Pycock, B.Vet.Med., Ph.D., D.E.S.M., M.R.C.V.S.

Equine Reproductive Services, Messenger Farm, Ryton, Yorkshire

The mare illustrated here is presented to you four hours after foaling. The owner is worried about the fact that the mare has not yet expelled her placenta, and poses five questions:

Answers:

What is the usual post-partum time for placental expulsion?

The average time needed for placental expulsion is about one hour and should not take more than two hours. However, there is debate amongst equine clinicians with respect to the time interval in this definition and recognition of the precise time at which the process has become pathological is difficult. Most clinicians consider the fetal membranes to be retained if they are not passed within three hours of birth. Retention of the fetal membranes (RFM) is one of the most common peripartum problems in the mare, with an incidence in the range from 2% to 10%.

What can be the sequelae of retained fetal membranes?

RFM is properly regarded by veterinary surgeons as a potentially more serious affection than the same condition in cattle. This has originated from the times when draught horses predominated in the horse population and was invariably followed by serious sequelae; as a result early manual removal was the rule. Complications include acute metritis, septicaemia, laminitis and even death. With prompt and effective treatment these sequelae can be avoided. In many cases, uterine involution is delayed even if these more serious complications do not develop. The riding horses and ponies of today are less likely to suffer from these complications, but RFM should be treated as an emergency.

What is thought to be the cause of retained fetal membranes?

The precise cause of retained fetal membranes remains unclear. The most likely is uterine inertia due to hormonal imbalance. Oxytocin has an important role in postpartum uterine contractions and low levels of this hormone in the circulation may result in abnormal myometrial activity. This in turn leads to placental retention. The incidence of RFM is much higher incidence after dystocia, which is probably due to either uterine trauma or uterine inertia. In a retrospective review of equine dystocias treated at the Ghent Veterinary School, there was an incidence of 28% after fetotomy and 50% after caesarean operation; in the latter, the likelihood of retention was doubled if the foal was alive at the beginning of the operation compared with when it was dead1. These authors emphasise the branching nature of the numerous chorionic microvilli which interdigitate strongly with the corresponding labyrinth of endometrial crypts. The microvilli are better developed in the uterine horns than in the body and are considerably more branched, as well as bigger, in the nonpregnant than in the pregnant horn. This latter property of the villi, coupled with the more marked folding of the allantochorion and endometrium as well as the slower involution of the non-pregnant horn, all combine to provide an explanation of the higher incidence of retention in the non-pregnant horn. Placental pieces from other areas can be retained and it is important to thoroughly examine the fetal membranes to determine which portion has been retained (see image at left). The most frequently retained portion is the tip of the non-pregnant horn. The tip of the pregnant horn is generally more oedematous and smoother when compared with the non-pregnant horn. Often the horns of the placenta are torn and it may be difficult to decide whether some membrane is missing and has been left inside the mare or not. A through examination is essential in cases of doubt and the mare should be carefully monitored over the subsequent 48 hours to check for any untoward signs.

How would you treat this condition?

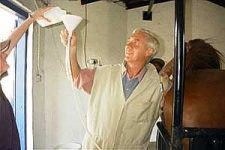

The most obvious sign of a retained placenta is the appearance of a variable portion of the placenta protruding from the vulval opening. Less commonly no placenta may be visible. This either means that no part of the placenta has been passed or, more likely, portion of the placenta remains attached. The placenta should initially be tied up in order to prevent touching the hocks. As uterine contractility plays an important role in the dehiscence of the fetal membranes administration of oxytocin is recommended as a first and many times (up to 90% of cases) successful treatment. It is a good rule not to wait longer than 6 hours after delivery (depending of the case history or in heavy breeds earlier is preferable) before such a treatment is started. This treatment avoids manipulation in the uterus with the risk of introducing microorganisms. Oxytocin can be given via the intramuscular route (20-40 iu), which can be repeated after one hour if the placenta has not been passed. Alternatively, use slow intravenous infusion of 50 iu oxytocin in 1 litre of physiologic saline during one hour. Symptoms of colic often follow injections of oxytocin and commonly precede natural expulsion so that pain-relieving drugs and sedation may be required. Only if this treatment fails and the placenta is almost detached but retained within the uterus should one attempt gentle manual removal. This interference should be carried out with scrupulous regard to asepsis, and no undue force should be applied, for even moderate traction on the afterbirth may cause the uterus to become inverted and prolapsed. In most cases of retention some separation of the allantochorion has occurred and consequently a variable amount of the afterbirth hangs down from the vulva. The mare is effectively restrained and measures taken to protect the operator from being kicked. The tail is bandaged and held to one side by the attendant while the obstetrician thoroughly washes the perineum and rear of the mare. With the hand and arm protected by a clean plastic sleeve, the extruded mass, or failing that the freed part lying within the vagina, is grasped and twisted into a rope. The gloved hand, anointed with lubricant is gently introduced along the ‘rope’ to the area of circumferential attachment in the uterus. As the ‘rope’ is gently pulled and twisted, the tips of the fingers are pressed between the endometrium and the chorion. The villi are easily detached, and as the allantochorion is gradually freed it is taken up by further twisting of the detached mass. The allantochorionic membrane is gently separated from the endometrium by moving one of the hands between them. The tightest attachment usually is at the tip of the horn. The process of separation usually proceeds quite smoothly, and the complete sac of allantochorion can be gradually detached from the pregnant horn. There is a tendency for attachment to be firmer in the non-pregnant horn, and occasionally retention is confined to this horn. If it is found impossible to detach the apical portions of the allantochorionic sac without tearing the membranes it is better to desist and to try again in 4-6 hours, by which time a successful outcome will be likely. Unwanted side effects of this manual removal may be serious haemorrhage, invagination of one of the horns and a higher chance of retention of microvilli in the endometrium. Vandeplassche and his colleagues1 refer particularly to the residue of microvilli which is present in the endometrium even after a normal expulsion of the afterbirth and which is vastly increased when manual removal is effected in a case of retention. During a difficult manual removal only the central branches of the chorionic villi are removed while practically all the microvilli are broken off and retained; rupture of endometrial and subendometrial capillaries may also occur. The consequences of difficult removal are: increased puerperal exudate, containing much tissue debris; endometritis and laminitis; uterine spasm and delayed involution of the uterus. It is for these reasons that Vandeplassche and his colleagues1 prefer to treat severe equine retention by means of intravenous drip administration of oxytocin rather than by persistence with manual removal. A third method described in the literature and which has may be successful under circumstances is the placement of some 10 L of warm, sterile saline inside the chorioallantoic membrane. Stretching of the uterine wall and stimulating uterine contractions via endogenous oxytocin may assist the separation of the microvilli from their endometrial crypts. This treatment should be used in combination with exogenous oxytocin administration. After removal, it is always important to check the placental membranes for completeness confirming that all the allantochorion has been removed. If pieces of membrane are left in the uterus they are usually impossible to reach due to the disproportionate size of the immediate post-partum uterus compared with the veterinarians arm. If necessary, the uterus should be flushed and siphoned to remove any fluid exudate remaining in the uterus by using a stomach tube and funnel.

Uterine lavage consisting of infusion of warm sterile saline using a stomach tube and funnel. This dark detritus should then be siphoned out.

Aftercare includes (depending on the severity of the case) regular general examination, checking the uterus (for involution and contents) and, if indicated flushing and siphoning the uterus once or twice daily for a few days in combination with further injections of oxytocin. The rationale for uterine lavage is to remove both debris and bacteria from the uterus. Warm, sterile physiologic saline should be used in two to four litre flushes (until the recovered fluid is clear). Vandeplassche and colleagues1 deprecate the use of any antiseptic solution to rinse the uterus after the expulsion of the afterbirth, because this depresses phagocytosis. Special attention is paid for signs of laminitis and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are given when laminitis is a suspected complication. Tetanus antitoxin is recommended. and, if indicated, treatment with antibiotics. If there is a risk for the mare developing a toxic metritis, she should be treated with systemic and intrauterine antibiotics. The dominant infective organism is often Streptococcus zooepidemicus initially, but infection with gram-negative bacteria such as Escherischia coli frequently develops. The antibiotics chosen should have broad-spectrum activity and should be effective against endotoxin-producing organism. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors such as flunixin meglumine should be given to either treat or minimise the risk of development of endotoxaemia.

What is the reproductive prognosis for the mare?

Provided treatment is begun at the correct time and no secondary complications develop the prognosis for a case of retained placenta is good. Mares that have had RFM should not be mated at the foal heat as the chance of conception is reduced.

References

1: Vandeplassche, M., Spincemaille, J., Bouters, R. and Bonte, P. (1972) Equine Vet. J., 4, 105.

© 2002 Dr. Jonathan F Pycock, B.Vet.Med., Ph.D., D.E.S.M., M.R.C.V.S.

Presented here with the authors’ permission.