The Dirty Mare

By Dr. Jonathan F Pycock, B.Vet.Med., Ph.D., D.E.S.M., M.R.C.V.S.

Equine Reproductive Services, Messenger Farm, Ryton, Yorkshire

Introduction

One of your main objectives whether owning or working with brood mares should be to produce the maximum number of live, healthy foals from the mares bred during the previous season. Perhaps the biggest obstacle to achieving this aim is the problem-breeding mare. The biggest category of problem breeding mare is the so-called “dirty mare”. Mare owners frequently have a “dirty mare” from which they want to breed. Breeding farm personnel and veterinarian must be able to help maximise the chance of this wherever possible. Commitment from both mare owner, breeding farm staff and veterinarian is needed and the owner should be made aware of this at the outset and given a realistic expectation as to the chance of success. This topic will consider the “dirty” mare and how to provide an effective management. Particular emphasis will be on the mare susceptible to persistent post-breeding uterine infection.

Failure to conceive

Many mares that cycle, but fail to conceive have infections in their reproductive tracts. Hence they are sometimes called “dirty” mares. Whilst the term “dirty mare” is in common usage in breeding, it is not always appreciated that there are several categories of dirty mare. All dirty mares either have, or are at risk for, inflammatory changes involving the endometrium (lining of the uterus). This is the reason that dirty mares are said to have an endometritis (literally: inflammation of the endometrium or lining of the uterus). As you know the uterus is the place where the early pregnancy will develop. Mares with endometritis may either fail to conceive in the first place or will undergo early loss of the pregnancy.

Broadly, dirty mares fall into the following categories:

- mares with acute infectious endometritis

- mares with chronic (long-term) uterine infection often with scar tissue

- mares susceptible to persistent mating-induced endometritis

Acute infectious endometritis

An important contributory factor to infection can be poor vulval shape. In the normal mare the vulva provides the first effective barrier to protect the uterus from ascending infection. The vulval lips are full and firm and meet evenly in the midline and there is 80% or more of the vulval opening below the brim of the pelvis (Figure 1a). If the vulval seal does not work properly, sucking of air and contamination into the vagina can occur (Figure 1b). The initial vaginitis may lead to acute uterine infection resulting in a dirty mare.

Diagnosis of endometritis can be made by collection of concurrent endometrial swab and smear samples during early heat for bacteriological culture and cytological examination, respectively. This allows time for resolution prior to breeding, and maximises the chances of pregnancy. The ideal technique should ensure that the swab enters the uterus and collects bacteria from only the uterine lumen. It is important to ensure that the method of swabbing does not introduce bacteria into a previously normal uterus. A positive culture result, with no evidence of inflammatory cells in the smear (usually neutrophils), is likely to be due to contamination during collection.

Acute infectious endometritis is found most frequently in older mares that have had several foals. Such mares have a breakdown in uterine defence mechanisms that allows the normal genital flora to contaminate the uterus and develop into persistent endometritis. The approach to treatment most favoured by practitioners has been the infusion of various antibiotics, dissolved or suspended in water or saline, into the uterus. The number of treatments required depends on individual circumstances, but daily infusions for 3 to 5 days during oestrus works well in most cases.

Predisposing causes to the persistent endometritis, such as defective vulval conformation, should also be attended to, with suitability of a Caslick’s procedure being considered.

Chronic uterine infection

These mares have a wide range of degenerative changes (fibrosis (scar tissue) and glandular degenerative changes) and the infection has often been present for a long time. Successful treatment of this category of dirty mare is difficult. Improved fertility after endometrial curettage has been reported. This has involved the use of mechanical and chemical agents (namely povidone-iodine and kerosene) that cause endometrial necrosis. This treatment, apart from being of questionable value, can cause irreversible damage such as adhesions. Repeated daily lavage with 2 to 3 litres of hot (50°C) sterile, isotonic saline has been suggested as a method of reducing the size of the lymphatics and thereby the whole uterus. The prognosis for fertility remains poor whatever treatment is used.

Persistent mating-induced endometritis (delay in uterine clearance)

Persistent mating-induced endometritis has come to be recognised as the major reason for failure of mares to conceive. This means it is the most important category of dirty mare.

The inflammatory response to semen

Semen is deposited directly into the uterus when mares are bred. This means that bacterial and seminal components as well as debris contaminate the uterus that results in uterine inflammation. It was previously thought that the inflammatory response to breeding was due to bacterial contamination of the uterus at the time of insemination. It is now accepted that the sperm themselves, as well as bacteria, are responsible for the acute inflammatory response in the equine uterus after insemination

A transient uterine inflammation following insemination is useful and serves to clear the uterus of excess sperm and debris associated with breeding. In most mares this transient endometritis resolves spontaneously within 24-72 hours so that the environment of the uterine lumen is compatible with embryonic and fetal life.

However, if the endometritis persists more than 4 or 5 days after ovulation, this is incompatible with embryonic survival. These mares are referred to as susceptible and they develop a persistent endometritis.

The physical ability of the uterus to eliminate bacteria, inflammatory debris and fluid is known to be the critical factor in uterine defence. It is a logical conclusion that any impairment of this function i.e. defective uterine contractility renders a mare susceptible to persistent endometritis.

Detection of the susceptible mare

This can be difficult as there may only be subtle changes in the uterine environment, not readily detected by current diagnostic procedures. Many mares show no signs of inflammation before mating, but will fail to resolve the inevitable endometritis which follows mating. Use of ultrasound to detect uterine fluid has proved useful to identify mares with a clearance problem (Figure 2).

How to breed these mares

Management must be excellent prior to breeding:

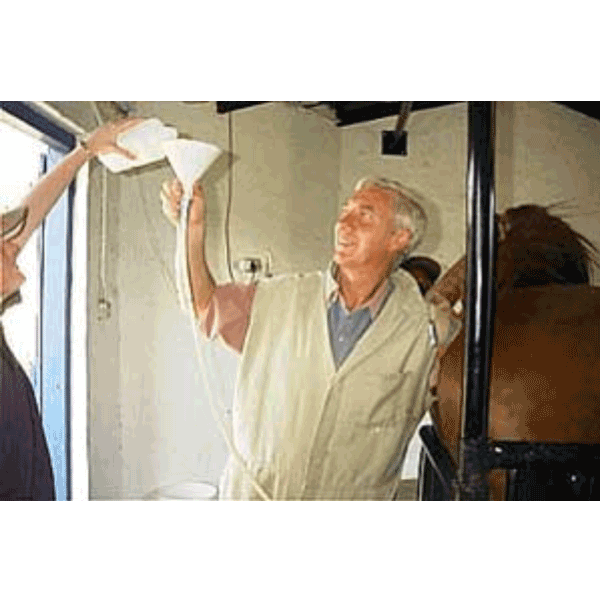

- Hygiene: good hygiene at foaling is essential and all mares should be thoroughly examined postpartum for the presence of trauma which might compromise the physical barriers to uterine contamination. Gynaecological examinations, particularly of the vagina, should be performed as aseptically as possible. Attention to hygiene at mating by using a tail bandage and washing the mare’s vulva and perineal area with clean water (ideally from a spray nozzle which avoids the need for buckets) (Figure 3).

- Correct timing of breeding: breeding should occur at the optimal time and the number of breedings should be restricted to one. This means that these mares need very close monitoring of the heat period by rectal palpation and ultrasonography. The use of ovulation induction agents is strongly recommended in such mares in an attempt to ensure they are only bred once. Prediction of ovulation can also be made easier by not breeding these mares too early in the year i.e. before they have begun to cycle regularly. If feasible, the use of artificial insemination can be helpful to reduce (but not eliminate) the inevitable post-breeding endometritis.

- Ultrasound evaluation of the uterus: for detection of intraluminal uterine fluid, in addition to conventional techniques of endometrial cytology and bacteriology, before breeding. Even if cytology and bacteriology have been negative before breeding, mares susceptible to postbreeding endometritis usually accumulate fluid in the uterine lumen for more than 12 hours after breeding.

- Correction of any conformational defects

- Treatment regime

A single breeding must be arranged 1 to 2 (or even 3) days before the anticipated time of ovulation. It is my experience that most stallion spermatozoa are viable at least 48-72 hours after breeding. This early breeding allows more time for drainage of fluid via an open estrous cervix and also utilises the natural resistance of the tract to inflammation during estrus. It allows sufficient time to flush the mares more than once before ovulation if necessary. In the author’s opinion, treatment for endometritis is ideally performed before ovulation. Progesterone concentrations rise rapidly in the mare and any post-ovulation treatment has an increased risk of uterine contamination. In addition, uterine fluid is less likely to drain if the cervix is beginning to close.

After Breeding:

- Doses of oxytocin are given every four to six hours after breeding. Ultrasound examination of the uterus the following day after breeding is performed to assess the amount of any intrauterine fluid. If more than 2 cm of fluid is present in the uterine lumen, lavage of the uterus with 1-2 litres of warmed, sterile saline using a uterine flushing catheter is performed (Figure 4). During lavage, oxytocin should be given. In cases where the cervix has failed to relax adequately, digital dilation of the cervix, with scrupulous attention to cleanliness, is indicated.

- This is followed by infusion of antibiotics where considered appropriate, with awareness of the risks of increasing antibiotic resistance or creating a potential superinfection situation. In recent years as knowledge of these risks have increased, in the absence of a previously identified uterine pathogen, lavage with a non-antibiotic solution has become far more popular and is considered to be efficaious while present fewer risks.

- Further doses of oxytocin are given every six hours.

- In some mares, the slower release of prostaglandin may be useful in addition to oxytocin. A single prostaglandin injection should be given some 6 to 8 hours after the first oxytocin injection.

- The mare is re-examined the following day and oxytocin treatment repeated if fluid is still present. Only rarely will a second infusion of antibiotics or lavage procedure be performed due to the risk of uterine contamination

- An important concept is to treat in relation to breeding and not wait for ovulation.

Conclusion

A dirty mare, once inseminated or bred should not only be checked for ovulation but also for fluid accumulation in the uterus, one of the most reliable clinical signs of susceptibility to post-breeding endometritis. If a mare is recognised as being susceptible to persistent mating-induced endometritis, intensive post-breeding monitoring and treatment is necessary in order to improve the chances of conception.

© 2003 Dr. Jonathan F Pycock, B.Vet.Med., Ph.D., D.E.S.M., M.R.C.V.S.

Presented here with the author’s permission.