Equine Viral Arteritis (EVA)

aEquine-Reproduction.com LLC, Wynnewood, OK 73098, USA;

bDepartment of Veterinary Science, Gluck Equine Research Center, College of Agriculture, Food and Environment, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40546, USA (Retired)

Equine viral arteritis (EVA) is not a new disease, but one that most breeding farms are either not aware of or do not fully understand. The disease often causes near-panic among horse breeders when they initially learn about it. To reduce apprehension and concern about EVA, it is important that breeders become more educated about the disease and its potential economic consequences. With knowledge will come a greater degree of understanding and awareness of how to control the disease. Except for young foals, EVA is typically not fatal in the otherwise healthy individual. It does however have the potential to cause a significant, if localized negative economic impact. EVA only affects equids and is not a disease of other species, including humans.

There is often confusion about the abbreviations – “EVA” and “EAV”. “EVA” is the abbreviation for the disease – equine viral arteritis – whereas “EAV” is the abbreviation for the causal virus – equine arteritis virus. EVA is primarily a viral respiratory infection, and as such is transmitted via the respiratory route through direct contact with an infected individual. An acutely infected stallion will also shed the virus in its semen and if bred to a mare by natural cover, be capable of transmitting infection concurrently both by the venereal as well as the respiratory route. The acutely infected non-pregnant mare can shed EAV for 6-10 days via the reproductive tract and could therefore serve as a source of infection. To a lesser degree it can also be spread indirectly by contact with virus-contaminated tack, breeding shed equipment and even on the hands and clothing of persons handling infective material, such as a case of EVA-related abortion, or semen from a carrier stallion. It is important for every horse breeder to have a clear understanding of the disease as it has the potential to significantly impact the breeding animal, principally as a cause of contagious abortion and also in giving rise to the carrier state in a variable percentage of infected stallions. It is these two outcomes of EAV infection that are the source of greatest misunderstanding and panic among breeders on their first encounter with EVA.

What is often not appreciated is that the majority of horses do not exhibit any clinical signs of disease following first-time exposure to EAV. This can be a cause for major concern, as it means that horses may come in contact with other horses that are in an infectious state unbeknownst to the horse owners who clearly are totally unaware of the situation. Horses that do become clinically affected with EVA may present with any combination of the following: elevated temperature, depression, loss of appetite. They may also exhibit edema in the lower limbs, especially the hind limbs, mammary glands, scrotum, sheath, around or above the eye, lethargy, stiff movement, nasal discharge, conjunctivitis (“pink eye”) and a localized or generalized skin rash.

Reproductively, the repercussions of equine viral arteritis (EVA) can be economically very damaging as unprotected pregnant mares that become infected with the virus are at significant risk of losing their pregnancies, typically within the following 30 days, i.e. either late in the acute phase or early in the convalescent phase of the infection. Abortion rates among groups of susceptible mares can vary, but the potential exists for an “abortion storm” to occur with abortion rates as high as 50 to 70 percent. Stallions that become infected may continue to harbor the virus in certain of their secondary sex glands long after they have recovered from the acute phase of the infection, and become permanent semen shedders and carriers of the virus. As this is a virus rather than a bacterium, there is no known fool-proof means of preventing transmission of EAV in semen – use of antibiotics will not have any effect. Additionally, freezing will not destroy the virus. Transmission of infection can take place through breeding to a carrier stallion via live cover, or the use of A.I. with raw, fresh cooled or frozen semen.

Attempts to mechanically remove the virus from semen have not produced absolute results. Morrell et al used several modifications of single-layer centrifugation (SLC, SLC with an inner tube and double SLC) through Androcoll-E, a species-specific colloid to evaluate their ability to separate spermatozoa from virus in ejaculates from carrier stallions. The three types of SLC significantly reduced the virus titer in fresh semen at 0 h and in stored semen at 24 h (p < 0.001) but did not completely eliminate the virus.[1] Limited research has demonstrated success with elimination of viral shedding in stallions. Miszczak et al showed successful cessation of viral secretion in a cohort of 16 naturally-infected stallions. This was as a result of testosterone suppression following anti-GnRH vaccination(s). It should be noted that this effect was not immediate, and indeed the following breeding season, some stallions were still shedding virus. All the stallions were EAV negative at month 22, with one stallion being vaccinated a third time at month 15. Some stallions also showed a permanent reduction in testosterone levels which may impact breeding ability and adequate sperm production.[2]

In a “worse-case scenario”, an unprotected mare could be bred with EAV-infective semen, and following breeding, be turned out in a pasture with other mares that are already pregnant and never previously exposed to EAV. The mare bred with infective semen may or may not develop signs of EVA (if she experiences an asymptomatic infection, the owners will not be aware of the situation) and she may well infect other mares in the herd. As these other mares are already pregnant at time of viral exposure, widespread abortion can result. This is a worse-case scenario, which though it may seem improbable, regrettably has occurred on repeated occasions in the past. Where they occur, outbreaks such as these give rise to increased awareness of EVA and alarm within the horse breeding community; it is an expensive lesson, however, of becoming educated about the realities of infection with this virus.

A less dramatic result might be if an unprotected mare is bred with EAV-infective semen and experiences an asymptomatic infection. She may not conceive on that cycle or alternatively, she may lose the pregnancy as a result of early embryonic death. When she is rebred on a subsequent cycle, she will have acquired immunity to EAV, and should conceive barring any other intercurrent factor(s) that could interfere with establishment of pregnancy. Under such circumstances, the mare’s owner will have no reason to be aware that the mare had been exposed to the infection.

Management of equine viral arteritis (EVA) bears out the old adage “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”. Excellent protection against EVA can be achieved by vaccination against the disease. With the exception of the USA, ALL horse-breeding countries have controls in place debarring the importation of carrier stallions or virus infective semen. Some have developed specific protocols to be followed in the event of an outbreak of the disease. Surprisingly, the USA is the only one of 64 Thoroughbred racing countries world-wide that has no testing requirements or restrictions in place to prevent importation of the virus, nor does it have a national program for the prevention and control of the disease. In the USA, proactive and reactive measures are left up to the individual states and the industry. Such measures are currently lacking in the vast majority of states. It is surprising that while a negative “Coggin’s” test for equine infectious anemia is required for interstate shipment of a horse, an EAV carrier stallion can be freely transported without meeting any requirements or prior notification. Similarly, EVA is not a “reportable disease” in all states, so neither the state animal regulatory officials nor mare owners are aware when a carrier stallion or virus infective semen is shipped into that state. For several years, efforts have been ongoing aimed at providing greater protection against EVA for breeders in the USA. It is hoped that these efforts will come to fruition in the near future.[3]

Certain horse breeds in some countries have a higher prevalence of antibody positive animals in their respective populations than others. This has led to the perception that EVA is pervasive and not worth worrying about, based on the assumption that such animals are likely exposed to the infection early in life, and develop the desired degree of immunity. Due consideration is not given, however, to countries and breeds in which there is a low level of infection with EAV. The onus is placed on those countries to protect their animals from the introduction of the virus from countries in which EAV infection is known to be prevalent. Like all other ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses, EAV has the ability to mutate naturally and give rise to new strains of varying antigenicity and pathogenicity. While, thankfully, the current vaccine would appear to be broadly protective against strains of the virus in current circulation, it is possible that a virus strain could arise at some future point that is significantly different with respect to its antigenicity and against which the current vaccine may not offer an adequate level of protection.

There are two commercial vaccines against EVA – one, a modified live virus vaccine is only available in North America, and the other an inactivated vaccine is only approved for use in certain countries in Europe. In many countries (and even in individual states within the US!) vaccination is either not allowed or viewed with considerable disfavor. It is important that owners and breeders be aware that once a horse has been vaccinated against equine viral arteritis (EVA), a subsequent blood-test will likely detect antibodies to the virus from vaccination in that individual. Currently, it is not possible to determine if those antibodies are the result of natural exposure to the virus or from vaccination. It is for this reason some breeders are reluctant to vaccinate against this disease, fearing that it will compromise their ability to export that animal at a later date. If a blood test turns up a positive result for antibodies to EAV, the animal can be re-sampled two to three weeks later to determine whether the initial antibody level is stable or declining. If stable or declining, this confirms that the horse is not in the acute phase of the infection (the infectious state in the mare lasts about 10 to 21 days) and does not represent a risk of spreading EAV to other unprotected horses it might come into contact with. On the other hand, if a stallion is found positive for antibodies in its blood and there is no certified history of vaccination against EVA and of the stallion being confirmed antibody negative at time of vaccination, then a test should be carried out on its semen to determine if that individual is a carrier of EAV. Detection of virus in the semen is indicative that the stallion is a shedder and carrier of the virus. Additional management measures involving such a stallion are strongly recommended if he is to be used for breeding. On the other hand, if no virus is found in the semen, the antibodies found in the blood resulted from previous vaccination or from natural exposure to infection and are not indicative that the stallion is a carrier. Adequate documentation of a negative pre-vaccination blood test is essential when investigating such situations. While the major horse-breeding countries (USA, Australia and New Zealand, Japan and the EU member states) require a negative virus isolation test on the semen from a stallion testing antibody positive in its blood, a limited number of countries e.g. in Central and South America, the Caribbean and the Far East, refuse entry to any horse – mare, stallion or gelding or otherwise, based solely on a positive blood test result, even if there is certified proof of vaccination against equine viral arteritis (EVA). It is therefore important to confirm what regulations are in place for any country to which a stallion or his semen might be exported at some future point prior to vaccination of that stallion. It should be emphasized that vaccination will not interfere with export of horses to the vast majority of the world’s horse breeding countries, including the Member States of the European Union.

Vaccination protocols are simple, although as noted above, some countries and States discourage or do not permit vaccination against EVA. In the authors’ opinion such discouragement or prohibition is short-sighted in countries/states in which the virus is known to exist. It may well contribute to a future major EVA outbreak following the illegal or inadvertent introduction of the virus to the unprotected resident horse population of those countries/states. The only exception to the aforementioned would be where a country is confirmed to be historically free of any evidence of circulation of EAV, e.g. Japan, and most recently, New Zealand, and where they wish to maintain their total freedom from this infection.

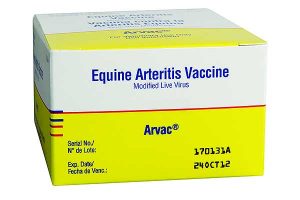

In the case of the mare, a pre-vaccination blood test for antibody determination may be performed and if antibodies are present at sufficient levels, vaccination may not be considered necessary. Alternatively, a mare may be vaccinated without first evaluating her antibody status for EAV. As previously stated, the only vaccine available in the USA and Canada is a modified-live virus vaccine “Arvac®” (originally developed by Fort Dodge Animal Health, Overland Park, KS USA, but subsequently manufactured by Zoetis Inc., Florham Park, NJ USA). Supplies were limited at the time of the 2006 multi-state occurrence of EVA which primarily affected the Quarter Horse industry. With increased production of the vaccine after the outbreak, availability of adequate supplies of the vaccine would for a while no longer be a problem. Availability of “Arvac” today however remains variable. In 2018 the manufacturer announced discontinuation of Canadian production. In the USA, Arvac is often announced as being on “backorder” by distributors and retail stores.

In certain European countries, an inactivated virus vaccine “Artervac®” (also manufactured by Zoetis Inc.) has been licensed for use. Although this vaccine has not been shown to be as potent in stimulating an immune response as the modified live virus vaccine, it is safe and offers some degree of protection. A minimum of two inoculations of Artervac® are recommended to achieve adequate protection levels. Vaccination of mares with the modified live virus vaccine Arvac® should be carried out when the mares are not pregnant. This vaccine is not recommended by the manufacturer for vaccination of pregnant mares, especially during the last two months of pregnancy. It has been suggested however that in the face of an outbreak of EVA where there is significant risk of pregnant mares being exposed to the disease, the risk of possible adverse effect from vaccination is significantly less than the risk of abortion from natural infection with the virus. Following first time vaccination with Arvac® (which requires only a single initial injection with an annual booster), it is recommended mares be isolated for 21 days to enable them to develop a serviceable level of immunity and to avoid the very slight possibility of transmission of the vaccine virus. Since it is a modified live virus vaccine, a variable percentage of first-time vaccinated animals will shed the vaccine virus for a very short period of time, in most cases, within the week following vaccination.

In the case of stallion vaccination, the protocol is a little more complicated. Firstly, it is essential to demonstrate that the stallion was not a carrier of EAV prior to vaccination. To confirm this, it is necessary to obtain a blood sample for testing for antibodies at the time of – immediately prior to – vaccination. It is recommended that at least two vials of blood be collected, the serum harvested, one of the samples sent to a laboratory of established testing proficiency, and the other stored by the veterinarian, preferably at -20°C, until the laboratory results are available. A laboratory approved by the USDA or government agency for testing for this infection should be used so that the certification that the stallion was serologically negative for antibodies prior to being vaccinated is recognized and accepted. The advantage of obtaining more than one blood sample prior to vaccination is that, in the infrequent event that the sample sent to the testing laboratory is lost or damaged in transit, there is a back-up sample of serum available for testing. Blood drawn after vaccination will very likely test positive for antibodies to EAV. After blood is drawn, the stallion should be vaccinated and then isolated for 28 days. This prevents the possibility of the stallion coming into contact with a source of virus prior to him becoming immunized and protected against infection. The fact that the stallion tested negative and was subsequently vaccinated can be used to promotional advantage in marketing a stallion – it is not uncommon to see sport horse stallions advertised as being “EVA negative and vaccinated”. Annual booster vaccinations are recommended for both stallions and mares.

An integral part of any vaccination program against EVA should be vaccination of all colts between 180 and 270 days of age. Colts within this age group are pre-pubertal and very likely negative in their blood for antibodies to the virus; this should be confirmed by taking a blood sample at time of vaccination. By vaccinating at this young age, and with annual booster vaccinations, effective protection against EVA can be established and maintained. If this vaccination recommendation was widely implemented, in time, the incidence of EVA would be significantly reduced, and possibly eradicated through elimination of the carrier stallion population, which is the primary natural reservoir of the virus.

Successfully breeding a mare to an EAV carrier stallion for the first time is not overly complicated, but does require some forward planning. The mare must have been blood-tested and either have a sufficient level of EAV antibodies in her blood from previous natural exposure to the virus, or have been vaccinated and isolated prior to being bred to the stallion. It is necessary that vaccination takes place a minimum of three weeks prior to the breeding date to enable the mare to mount an adequate immune response. Stallion owners possessing EAV carrier stallions should disclose this fact to mare owners prior to the mare being booked for breeding. This has been the practice of at least one well known warmblood breeding farm that stands EAV shedding stallions. The intent is to ensure mares bred to such stallions have been vaccinated or been shown to have acceptable antibody levels prior to insemination with infective semen. Such ethical management practice is of major advantage to both mare and stallion owners and the industry at large by preventing the accidental transmission of EAV to unprotected animals and the risk of economically damaging outbreaks of EVA.

There are some common myths and misunderstandings connected with Equine Viral Arteritis (EVA):

Equine Viral Arteritis (EVA) is a fatal disease.

EVA is a fatal infection in foals congenitally exposed to the virus in the uterus of an unprotected mare that contracts EAV infection in late pregnancy. It can also occur in foals exposed to infection within the first few months of life. EVA is rarely fatal in older animals.

Geldings can carry and shed the virus just like stallions.

In order for the EAV to persist in the secondary sex glands of the male horse, testosterone must be present in adequate concentration in blood and tissues of the reproductive tract. Establishment and persistence of EAV shedding is a testosterone-dependent condition. As geldings do not have adequate levels of testosterone, they cannot become carriers and shed the virus. The only time a gelding can be infectious is during the acute stage of the infection, just like any other category of horse. Similarly, if a carrier stallion is castrated, he will cease to harbor and shed the virus within a period of several weeks as his testosterone levels diminish.

Equine Viral Arteritis (EVA) can be cured.

Presently, there is no specific antiviral treatment for EVA. It has been suggested that certain testosterone-suppressing treatments may result in permanent clearance of EAV from the reproductive tract of the carrier stallion. At this point, however, no medical treatment has been adequately validated for this purpose.[2]

Carrier stallions are contagious through non-sexual contact.

The only way a carrier stallion can transmit EAV is at time of breeding or masturbation when he ejaculates secretions from his secondary sex glands (where the virus is harbored). There is no evidence of shedding of the virus in any other bodily secretion or excretion.

Vaccinated stallions or semen from them are ineligible for entry into other countries.

All the major horse breeding countries will accept EVA vaccinated stallions or semen from them. However, antibody positive stallions are required to have a negative virus detection test on semen prior to entry. There are a number of minor horse breeding countries that refuse entry to stallions or semen from stallions that test positive on a blood test for EAV antibodies but are negative for the virus in their semen, regardless of whether their positive antibody status is the result of vaccination or natural infection.

Vaccinated stallions can shed the vaccine virus.

While there is a remote but never proven possibility that a stallion could shed the vaccine strain of EAV during the first week following first-time vaccination with the modified live virus vaccine, once that period has elapsed there is no possibility of such a stallion shedding the vaccine virus in his semen. Annual booster vaccinations are strongly recommended to maintain elevated antibody levels.

An EAV carrier and semen shedding stallion is always a carrier.

While a carrier stallion will not intermittently stop and restart shedding EAV in his semen, there have been a significant number of instances where a long term carrier stallion has spontaneously ceased shedding virus and never known to recommence viral shedding at a later date.

Mares that have been infected with the EAV will shed the virus after they have recovered.

As long-term persistence and shedding of EAV is testosterone-dependent, a mare is neither able to harbor nor shed this virus except while in the acute phase of the infection which may last up to 2 to 3 weeks.

Mares exposed to EAV may abort much later in pregnancy.

Abortion following exposure of unprotected pregnant mares to a source of EAV infection, if it occurs, will take place within a 30 day period following that exposure, i.e., late in the acute phase or early in convalescence. It is not the result of inseminating the mare with virus-infective semen.

I had a mare abort/newborn foal die, but we think it was due to “Rhino” not EVA.

Abortion or death in neonatal foals due to EAV closely resembles that caused by EHV- 1 and less frequently, EHV- 4 (both more commonly known as “Rhinopneumonitis viruses”). Accordingly, it is always advisable to submit appropriate specimens for laboratory examination to determine which viral infection is involved.

References and Footnote:

1: Morrell JM, Timoney P, Klein C, Shuck K, Campos J, Troedsson M. 2013. Single-layer centrifugation reduces equine arteritis virus titre in the semen of shedding stallions. Reprod Domest Anim 48(4):604-12

2: Miszczak F, Burger D, Ferry B. 2020. Anti-GnRH vaccination of stallions shedding equine arteritis virus in their semen: a field study. Veterinary Archives 90(6):543

3: Some states within the US – notably, but not limited to ID, MT, TX, UT and WA – have implemented animal or semen permit or declaration requirements related to EVA.

© 2007 & 2023 Equine-Reproduction.com, LLC

Use of article permitted only upon receipt of required permission and with necessary accreditation.

Please contact us for further details of article use requirements.

Other conditions may apply.