Contagious Equine Metritis (CEM)

History

In the spring of 1977 a previously unidentified genital infection of the equine was observed in the United Kingdom and Ireland in Thoroughbreds. Mares were being found not pregnant at a high rate; the diestrus period (the time in between “heats”) was found to be shorter than normal; and some mares were exhibiting a mucopurulent (pus) discharge. When the official breeding season ended on July 15th, approximately 200 mares had been infected on 29 farms involving 23 stallions1. Individual infection rates on affected farms varied from below 5% to 30% with many farms not breeding mares2.

CEM was confirmed in three countries in 1977 – The UK, Ireland and Australia – and it was thought that it possibly may have been the cause of a similar venereal disease seen in Ireland in 19763. In September 1977 Canada and the USA imposed a ban on the importation of potentially infectious horses originating in the UK, Ireland and France. CEM was however identified in both Kentucky (USA) and France in 1978, with the French outbreak involving horses other than Thoroughbreds. A subsequent outbreak occurred in Missouri (USA) in April of the following year. Control measures and treatment were quickly implemented, and the outbreaks eradicated. It has been estimated that the 1977/78 outbreaks cost the US horse industry as much as one million dollars a day, although others suggest a total cost of $60 million. Either way it can be seen that the potential for significant negative economic impact is great. Since that time there have been only occasional cases identified, usually in connection with animals that have been imported from outside the USA. The last cases prior to the current (2008) situation to be identified in the US were in 2006 in two Lipizzaner stallions that had originated in Eastern Europe.

Contagious Equine Metritis – CEM – Etiology

The causative agent of CEM is a microaerophilic gram-negative coccobacillus Taylorella equigenitalis in the family Alcaligenaceae. It was originally suggested that the organism be called Haemophilus equigenitalis4 but was ultimately named after the individual that identified it, Dr. C.E.D. Taylor. There appear to be two important strains of the organism (often referred to in abbreviation as the CEMO), one of which is sensitive to Streptomycin, and one of which is resistant. Both strains have the potential to cause epidemic venereal disease in susceptible mares.

Another species within the Genus Taylorella – Taylorella asinigenitalis – was identified as associated with donkeys in 20015. T. asinigenitalis is phenotypically similar to T. equigenitalis, but can be differentiated using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that utilizes especially designed primers. Some strains of T. asinigenitalis when transmitted to mares by live cover (it seems that T. asinigenitalis cannot be transmitted by AI, unlike T. equigenitalis) cause them to develop clinical disease similar to CEM, which can complicate diagnoses. T. asinigenitalis was recently identified in the reproductive tract of a stallion6, but this seems to be an isolated instance.

Equine death has not been associated with CEM, and the CEMO has not been seen to cause infection in humans.

Symptoms

Stallions are asymptomatic (no symptoms), but may carry the bacterium on their external genitalia for years, and therefore be persistent carriers and transmitters of the disease. In fact, to be technical, the stallion does not become “infected” with the CEMO, but rather harbours it in the manner of a commensal organism.

One of the first symptoms in a mare is likely to be that she is not pregnant after one or more breeding cycles. As was seen in the initial outbreaks of 1977/78, a commonality in many affected mares was “not pregnant”, with a premature return to estrus. It should be noted that although failure to establish pregnancy is a common sequela of infection, abortion is rare.

There are three categories of infection in the mare7:

- The acutely infected mare: This mare will present with an actively inflamed uterus, with an obvious milky-mucoid (pus) discharge from the external genitalia when she returns to estrus (and the cervix relaxes) – and quite often that return to estrus is earlier than anticipated.

- The chronically infected mare: This mare shows a lesser level of uterine inflammation, and an associated lower level of vulval discharge. It is likely that mares in this category will be more difficult to treat in order to clear the organism.

- The carrier mare: This mare shows no symptoms of the disease, but is harbouring the CEMO in the reproductive tract. This mare is more difficult yet to clear, and as a result of no obvious external signs represents a greater risk to the non-identified at-risk population.

The incubation period in the mare from the time of exposure to the onset of active symptoms (or diagnostic ability) is 2-12 days.

Contagious Equine Metritis – CEM – Transmission

As this is classified as an equine venereal disease, obviously the most likely method of transmission is through breeding live cover. This certainly seems to be an efficient method of transmission, as was evidenced during the outbreaks of the 1970’s. It is important to note however, that as the causative agent is a bacterium, other modes of transmission are also possible even in non live-cover situations. Poor biosecurity methodology is likely to be a major factor in these situations. The following includes practices that may result in, or increase, the likelihood of transmission in the face of T. equigenitalis presence:

- Not using a disposable AV liner;

- Sharing AV’s between stallions;

- Not cleaning AV’s adequately between use;

- Not using a disposable protective barrier on the rear of the breeding mount (where the penis contacts) during collection and changing it between stallions;

- Not washing the breeding mount with a suitable agent (e.g. Chlorhexidine) between stallions;

- Not using an antibiotic extender (or an antibiotic to which the organism is not sensitive) – it should be noted that even with the use of a suitable antibiotic, transmission may still occur;

- Sharing of penis washing equipment without sterilization in between stallions or good aseptic technique (this includes hands – e.g. use of disposable latex gloves when washing and/or guiding the penis that are then discarded, or thorough scrubbing of the hands in between collections/breedings with a suitable bactericide);

- Other poor sterility or aseptic technique associated with the collection/breeding process.

Mares that are bred with infective semen or become infected during the live-cover breeding process that do become pregnant may give birth to a chronically infected foal that harbours the pathogen until maturity, at which time – if breeding animals – they too may transmit the bacterium. Additionally, exposure by third parties may transmit the bacterium from those animals even if they are not breeding animals (e.g. the gelding owner that washes the gelding’s sheath, and then handles or breeds a mare or stallion may transmit the bacteria).

Diagnosis

Review of the symptoms above will produce a list of “first signs” that may be seen by the average owner/breeder. Diagnosis however cannot be made on clinical signs alone, as there are other bacteria – notably Streptococcus equi sub. zooepidemicus, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa – that are common and that may produce similar symptoms. Once the veterinarian is involved, diagnosis will be made by performing swabs and cultures of potentially affected parts. In the stallion the urethra, urethral fossa and diverticulum, and the sheath should be swabbed8 with the penis fully extended and erect, as well as if possible a sample taken of pre-ejaculate; in the mare culture sites will include the uterus (mucosal surface of the endometrium), clitoral fossa, and clitoral sinuses9 and also possibly the cervix. Pregnant mares can only have the clitoral sinuses and fossa swabbed, as internal swabbing would potentially compromise the pregnancy. Because all of these sites – especially those external – are commonly populated with significant contaminant growth of other bacteria, there is a risk of over-growth of the comparatively slow-growing T. equigenitalis. To attempt to reduce the risk of this overgrowth and exposure to light which may be detrimental to the bacterial samples, transport of the samples in Amies charcoal medium is recommended, maintained at 4° C or lower. If culturing is not to be performed within a few hours, freezing of the sample in the media may be considered, as it appears that it is not damaged by such action. There have been samples stored at -20° C for 18 years in Amies charcoal medium that have maintained viability10. Consultation with the laboratory that will run the cultures is recommended prior to freezing.

Swabbing of exudate may be of value for presumptive diagnosis11.

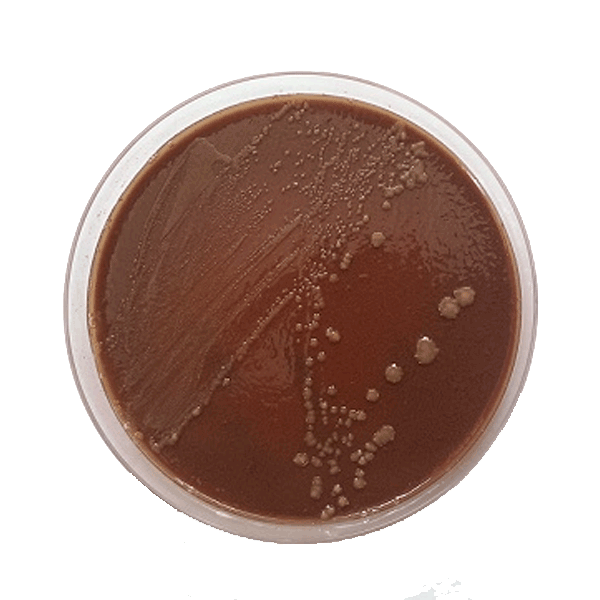

T. equigenitalis – a faculative anerobe – grows optimally on chocolate agar in a rich base at 37° C under 5-10% CO2. With 48 hours of incubation, colonies are likely to have a diameter of 1 mm that may enlarge further with longer incubation. The sometimes different sized and shaped colonies are usually shiny, smooth, grayish-white, and waxy. T. equigenitalis is oxidase, catalase, and phosphatase-positive, producing no acid from carbohydrates, and is unrelated to other gram-negative bacteria.

Recently a real-time PCR technique has been developed for detection of the CEMO and differentiation from T. asinigenitalis12, which may prove of value in increasing speed of diagnosis, and in cases of heavy overgrowth potential.

Blood samples may be taken from mares in order to submit them for a CEM complement fixation test. Stallions have not been seen to develop antibody presence, so there is no available blood test.

In addition to swabbing the stallion, he may be bred to two test mares that have been previously determined to be clear of T. equigenitalis. The mares are then swabbed at days 3, 6 and 9 post-breeding, and at or after day 21 blood is drawn for a CEM complement fixation test. The mares are again swabbed at or about day 28 post-breeding. If a stallion is determined to be positive at or after 21 days post-breeding the stallion is treated as below for 5 consecutive days.

Contagious Equine Metritis – CEM – Treatment

Treatment for both sexes is primarily topical with the intent of removing the offending organism and any smegma in which it may be located. Scrubbing the clitoral sinuses and fossa in the mare with a 4% solution of chlorhexidine for 5 consecutive days, following each daily treatment with packing of the area with a 0.2% nitrofurazone ointment (such as Furacin) is one protocol. An alternative treatment is 5 days of scrubbing with Betadine, followed by packing with Silvidine cream13. Systemic antibiotic treatment may be provided in conjunction with the topical cleansing. It should be noted that until the acutely infected mare has resolved internal tract presence of T. equigenitalis, there is little point in implementing external treatment. Indeed, according to Dr. P.J. Timoney (University of Kentucky, and a noted expert on CEM), there is a question as to whether such treatment of the acute mare may in fact exacerbate the carrier state with a higher degree of maintenance of the pathogen in the clitoral region. Repeated treatment of the mare is often required to eradicate the bacterium, so the mare is tested again 28 days after the last treatment, and if still positive a repeat of the treatment and testing is performed until found to be clear. In rare cases of persistent infection in the mare, surgical removal of the clitoral sinuses may be necessary. This was once a common part of treatment of the infected mare, but is now only used in extreme cases.

Treatment for the stallion is similar, consisting of thorough cleansing of the external genitalia, with the penis fully extended and erect. Additionally the urethral fossa and sinus are cleansed. A 2% Chlorhexidine solution is adequate for the stallion. It is recommended by some that following the Chlorhexidine wash, the penis be rinsed with sterile saline to avoid irritation7, this is not however included in other protocol recommendations13. Following this washing, the region is coated with 0.2% nitrofurazone cream or a similar ointment. Again, these treatments are continued for five consecutive days. Systemic antibiotics may also be used, oral Trimethoprim-Sulfa being suitable13. Once treated and tested clear, a stallion that previously tested positive for presence of T. equigenitalis will be required to test-breed two mares that were confirmed clear of the pathogen prior to that breeding. The mares are subsequently tested following breeding as discussed above under “diagnosis” to confirm absence of a carrier state in the stallion. If a mare tests positive for T. equigenitalis during the post-breeding testing, treatment and further testing of the stallion is recommenced, as well as treatment of the test mare. Most stallions however typically respond favourably to a single course of treatment, and are found to be clear upon the post-treatment test breeding.

Long-term Animal Effects

While there is short-term inflammation of the mare’s reproductive tract, with obvious potential for damage, as well as recorded instances of salpingitis, cervicitis and vaginitis1415, the long-term effect of such inflammation on fertility will be dependent upon severity, duration and the individual mare. Once cleared from the stallion, there is no evidence of persistent fertility issues.

Contagious Equine Metritis – CEM – Trade Restrictions, Detection Measures and Voluntary Screening

The major horse-producing countries, in particular those with established racing programs, all have CEM control measures in place to prevent the importation of semen or an animal carrying Taylorella equigenitalis, the CEMO. Ironically, some of those countries – particularly in mainland Europe – have a high presence of CEMO in their domestic horse populations, but this does not prevent an attempt to prevent importation of same. A coveted official status of “CEM-free” is accorded to many countries, including Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand. The USA has also possessed CEM-free status, but that may now (December 21, 2008) be under threat owing to the presence of 4 positive-testing stallions in the population at large, with the status of mares to which they have been bred and 14 other contact stallions being currently undetermined. A loss of CEM-free status may mean more restrictions for importation measures – more testing required in many cases – and in a few cases the possible refusal of entry. As CEM is a highly treatable problem however, and has in the past been eradicated, the hope with the current outbreak is that even if CEM-free status is removed, that it can be re-established in the near future.

The importance of CEM importation restrictions is significant, and directly related to the potential for negative economic impact in the face of an uncontrolled outbreak. The USA has good border biosecurity measures in place with regard to CEM, requiring testing of imported animals those who are shipping semen, with the only exception being Canada – which has similarly high import restrictions and CEM-free status. The effectiveness of the current importation measures is clearly demonstrated when one considers that between 1997 and 2003 the US allowed into quarantine 21 carrier stallions and mares (16 stallions, 5 mares) that had tested “clean” for the CEMO in their country of origin, but were then identified as carriers in US quarantine. All of these involved warmblood horses, with the majority coming from Germany. Canada faced a similar situation with 5 horses identified as not being the reportedly “clear” state of the exporting country upon testing during quarantine16. The situation came to a head with Canada in 2001 when a stallion was introduced into Canadian quarantine from Germany allegedly “CEMO free” only to be found to be a carrier. The Canadian authorities finally refused entry to further horses from Germany until they modified their testing procedures to more closely parallel those used in North America. The issue in this particular case was that CEMO swab cultures were grown for 7 days in Germany, but 14 days in North America, and the German results were not yielding organism presence, while the North American results were after a longer incubation period.

It is clear therefore that the importation criteria for entry into North America are adequate. What is of question is the domestic testing criteria. Some organizations in other countries have standard testing criteria for breeding stallions that are implemented at the beginning of each breeding season17. Had the index stallion in the December 2008 outbreak in Kentucky not been going through testing prior to having semen frozen for export, it is questionable if the outbreak would have been identified before a significant number of animals were infected. This does raise the question of whether there should be a mandatory testing protocol for breeding animals – specifically stallions – that needs to be performed at the beginning of each breeding season. Such a testing protocol could include screening of stallions for EVA and other pathogenic venereal diseases. It may be that this can only be a voluntary screening process, but it would demonstrate a responsible breeder if such a screening were performed and the results publicized in their stallion advertisements – and that in itself would be good publicity!

References:

1: Eaglesome MD, Garcia MM (1979) Contagious Equine Metritis: A Review; Canadian Vet. J. 20:8 201-206

2: Powell DG. Contagious Equine Metritis. (1978) Equine vet. J. 10: 1-4

3: O’Driscoll JG, Troy PT, Geoghan FJ. (1977) An epidemic of venereal infection in Thoroughbreds. Vet. Rec. 101: 359-360

4: Taylor CED, Rosenthal RO, Brown DFJ, Lapage SP, Hill LR, Legros RM. (1978) The causative organism of contagious equine metritis 1977: proposal for a new species to be known as Haemophilus equigenitalis. Equine Vet. J. 10: 136-144

5: Jang SS, Donahue JM, Arata AB, Goris J, Hansen LM, Earley DL, Vandamme PA, Timoney PJ, Hirsh DC. (2001) Taylorella asinigenitalis sp. nov., a bacterium isolated from the genital tract of male donkeys (Equus asinus); Int J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51(Pt 3):971-6

6: Båveruda V, Nyströmb C, Johansson K-E. (2006) Isolation and identification of Taylorella asinigenitalis from the genital tract of a stallion, first case of a natural infection; Veterinary Microbiology 116:4, 294-300

7: USDA-Aphis CEM Factsheet, 2005.

8: Swerczek, T.W. 1979. Contagious equine metritis – – outbreak of the disease in Kentucky and laboratory methods for diagnosing the disease. J. Reprod. Fertil. (Suppl), 27:361-365.

9: Simpson, D.J., and Eaton-Evans, W.E. 1978. Sites of CEM infection. Vet. Rec., 102:488.

10: Swerczek, T.W. 1984. Unpublished data.

11: Swerczek, T.W. 1978. The first occurrence of contagious metritis in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc., 173:405-407.

12: Wakeley PR, Errington J, Hannon S, Roest HIJ, Carson T, Hunt B, Sawyer J, Heath P. (2006) Development of a real time PCR for the detection of Taylorella equigenitalis directly from genital swabs and discrimination from Taylorella asinigenitalis; Vet. Microbiology 118:3-4; 247 – 254,

13: KY Department of Agriculture recommendations for CEM-exposed stallions. 12/19/08

14: AclandHM, Kenney RM. (1983) Lesions of contagious equine metritis in mares. Vet. Pathol., 20:330-341

15: Platt H, Atherton JG, Simpson DJ. (1978) The experimental infection of ponies with contagious equine metritis. Equine Vet. J., 10:153-159

16: Timoney PJ. (2003) The Continuing Threat to the US Horse Population Posed by CEM; Proc. NIAA Annual Meeting Proceedings

17: Horserace Betting Levy Board (UK) Codes of Practice on Equine Diseases

© 2008 Equine-Reproduction.com, LLC

Use of article permitted only upon receipt of required permission and with necessary accreditation.

Please contact us for further details of article use requirements.

Other conditions may apply.